#10 - Who REALLY owns 97% of the money supply, i.e., the new credit balances banks create "from thin air" as "loans"?

Rediscover your forgotten personal credit-creating power. [~13 minute read]

The view from the shoulders of a giant.

When Prof. Richard Werner examined the balance sheet of this small Raiffeisenbank at Wildenberg, Bavaria, before and after he took out an experimental €200,000 loan on 7th August 2013, he found hard evidence that debunked both the Fractional Reserve and Intermediation theories of banking (also called the Money Multiplier and Loanable Funds theories).

This was perhaps the greatest leap forward in our understanding of banking since Luca Pacioli invented double-entry accounting 500+ years ago.

His experiment effectively opened a new chapter in economics by demonstrating how the Credit Creation process works to produce bank loans. I believe Werner’s empirical evidence led the Bank of England to finally acknowledge this Credit Creation process in the main article1 in its 2014 Quarterly Bulletin (Q1).

Werner has also pegged the customer’s loan contract as a promissory note, a negotiable security with financial value equal to the principal amount promised, and this fact alone should be shouted from every rooftop to emphasise its importance.

As more people come to understand the ownership implications of Werner’s empirical findings, the public’s perception of banks is slowly changing.

My objective here is to support Werner’s ongoing efforts to correct the errors he has exposed in current banking policies and practices.

Figure 2 shows Werner discussing the results of his 2013 loan experiment at some key venues. I note three segments worth reviewing in these presentations (below) in which he introduces another novel claim, one not featured in the published papers describing his historic experiment.

2015: Rhodes Forum, from 9:31 to 10:20 [<1 min];

2017: Renegade Inc. “The Finance Curse”, from 17:30 to 19:20 [<2 mins] and

2023: UAE Capital Club, from 10:00 to 12:00 [2 mins].

His surprising new claim is that a bank “purchases” a customer’s signed loan contract. This can only mean that the newly created credit balance in the customer’s account becomes a payment to the customer, in exchange for the signed loan contract that the customer has given to the bank.

This novel claim is critically examined here for the first time, and, surprisingly, it turns out to be based on an underlying accounting mistake. It may seem like a trivial error, but it has far-reaching consequences.

On close examination, this new proposition is self-refuting. It implicitly assumes a specific payment by the bank that does not occur, as Werner’s evidence proved in 2013.

To make such a purchase, Raiffeisenbank must transfer €200,000 from one of its asset accounts2 to Werner’s Current account.

However, in each of the above videos, Werner insists that no transfer of €200,000 from any account ever occurred from anywhere, either inside or outside the bank, and Werner’s own evidence proves this assertion is correct.

In fact, the bank’s total assets increased by €200,000, proving no bank assets were transferred to Werner’s Current account. If they had been, the bank’s total assets would have decreased.

A bank can spend (or lend) its assets, which are always debit balances. But the demonstrated increase in Raiffeisenbank’s assets proves the opposite of a €200,000 outgoing transfer from a bank asset account (which Werner acknowledges).

The measured €200,000 increase in bank assets was due to the deposit of his €200,000 security.

Werner seems to have implicitly assigned original ownership of his newly created €200,000 credit balance to Raiffeisenbank, because that's the only way it could transfer ownership of it to him.

But both the published accounting records and simple logic refute that ownership assignment. Raiffeisenbank documents show that Werner alone owned the previously unseen €200,000 credit balance from the outset, as a creditor.

Consequences

Recognising this ownership assignment error means that:

Banks only own their debit balances and can’t own their credit balances;

The hypothetical purchase of a loan contract by a bank, using a newly-created credit balance, is impossible; and

In Werner’s experiment, a very valuable €200,000 security was deposited, increasing Raiffeisenbank’s assets; but the bank lent Werner nothing.

The fact that Werner’s €200,000 credit balance was newly created means it could not have had a prior owner. That’s what “newly created” means. This is not even accounting; it’s basic ontological reasoning. Such a never-before-seen €200,000 credit balance immediately belongs to the creditor named on the account where it first appears, viz. Richard Werner.

Werner’s deposit of his €200,000 security was the only transaction between Werner and the Raiffeisenbank on 7th August 2013. There was no purchase; only that deposit, and a very valuable one it was.

In effect, the bank’s acceptance of Werner’s deposit (a €200,000 security) forced Raiffeisenbank to create both a €200,000 debit and a €200,000 credit balance.

So, Werner’s €200,000 credit balance first appeared in his Current account, and, since it never existed anywhere else before it appeared in his Current account, nobody could previously have owned it, because it didn’t exist until it appeared in Werner’s Current account.

Ownership of Credit Balances

Credit balances are always bank liabilities, never bank assets, and if it doesn’t own Werner’s credit balance, it can’t spend it to buy anything. That is the simplest fact that refutes Werner’s “purchase theory”.

What does not yet exist cannot be owned.

Without Werner’s consent, the Raiffeisenbank couldn’t touch his new €200,000 because it was Werner’s asset and the bank’s liability at all relevant times.

Nobody can lend a liability

As the above-mentioned Bank of England’s Quarterly Bulletin article explains, a bank can only spend (or lend) its assets, which are always debit balances. Nobody can lend a liability, and if you don’t believe me (or the Bank of England), ask any competent accountant.

Common Law also supports Werner’s ownership of the new credit balance

In the common law, there is a principle known as the Nemo dat rule, a simple concept that also supports this accounting logic. The full principle, Nemo dat quod non habet, means, Nobody can give what they do not have.3 Since a bank can’t give (or lend) what it does not have, it can’t spend any credit balance.

Because Raiffeisenbank could never have owned a non-existent €200,000 credit balance, Werner is the only one who ever could have owned it, and he did own it from the moment it first appeared in his Current account.

It is now clear, it wasn’t a Loan! The only obligation Werner had to the Raiffeisenbank arose from his promise; it was not a debt obligation4 owed to the bank. A €200,000 debt would require the transfer of a €200,000 bank asset from the Raiffeisenbank to Werner, a transfer that did not happen.

“Houston, we have a PROBLEM!!”

This problem did not suddenly appear in 2013 during Werner’s experiment; it is centuries old and global in extent, infecting every “bank loan of credit”. Banks have been pretending to “lend credit balances” like this for centuries without anyone noticing this accounting anomaly. Since every so-called “loan” of a credit balance by a bank (a liability on its balance sheet) breaches the Nemo dat rule, it can only be a false pretence.

Since most people have little incentive to learn double-entry accounting rules, and few would even be able to detect this anomaly5, correcting it is up to those who understand accounting well. Perhaps someone as economically competent and influential as Prof. Werner will be able to apply their exceptional analytical expertise to investigating this ancient anomaly.

My Forensic Assessment

I suspect this ancient anomaly has escaped attention for centuries for the same reason that Werner’s novel claim of an impossible “bank purchase” process has gone unchallenged for about 10 years: namely, uncritical acceptance of the assumption that banks own the new credit balances they create. Nothing else could support centuries of lending such credit balances, or the alleged spending of them to purchase loan contracts. The evidence of this false pretence is easily visible once you acquire an understanding of basic accounting rules.

The Evidence:

1. False Pretences - exposed

Following the practical example set by Werner’s bank loan experiment, I’ve reviewed real bank loan account statements in my previous Substack articles #2, #3, #5, & #6, showing their typical modus operani, in which false pretences do create the appearance of bank ownership in real life, by falsely describing the customer’s real deposit of a valuable security as an impossible “bank withdrawal” from an EMPTY asset account.

Making such false and misleading entries in their accounts is the only way banks can achieve their deception; they must conceal the crucial role of depositors, who, like Werner, initiate a bank’s creative accounting process by depositing their valuable securities (mortgages). Their false words do transform a customer’s real deposit into an apparent bank withdrawal.

Having seen this modus operandi repeated (with slight variations) in three out of three cases I’ve examined in detail, I recognise a similar pattern of evidence in the published records of Werner’s 2013 experimental loan at the Raiffeisenbank.

2. Raiffeisenbank’s False Pretence

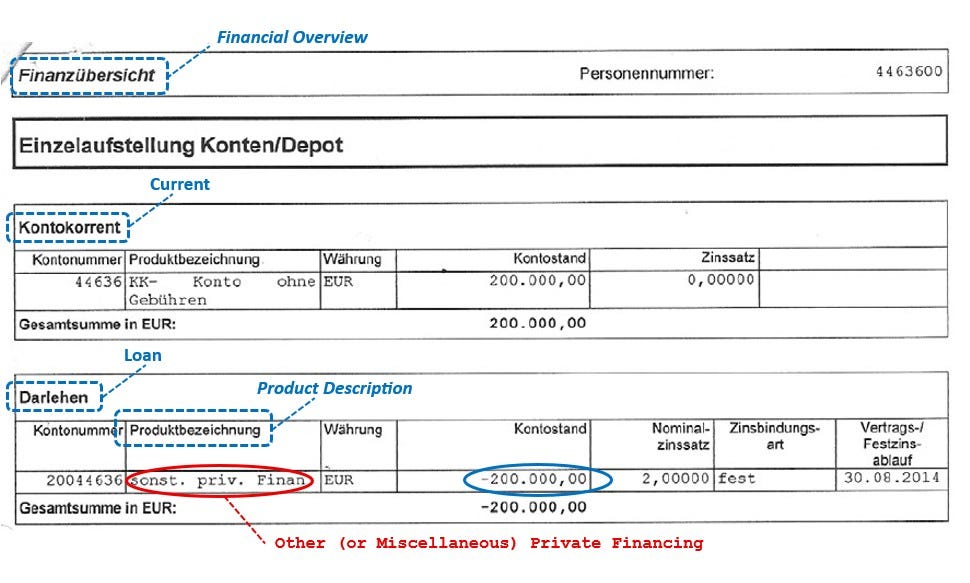

When Werner published his 2014 paper describing his loan experiment in detail6, he attached supplementary materials, one of which is entitled “Supplementary material 2. The account statement of the borrower”, which contains the evidence of false entries. That is a Raiffeisenbank document7, part of which is reproduced in Figure 3, with added translations of its relevant German text.

The bank’s deceptive pretence is highlighted in RED.

For clarity, Werner’s Loan account [Darlehen], showing a debit balance [-200,000.00], is also Raiffeisenbank's asset account. That asset was Werner’s deposited €200,000 Security.

Figure 3 shows how Raiffeisenbank misrepresents both the nature and source of its new €200,000 asset, under the heading Product Description [Produktbezeichnung] as Other (or Miscellaneous) Private Financing [sonst. priv. Finan].

A true account would describe the nature of the bank’s new asset as the €200,000 Security deposited by Richard Werner or, at least, identify Richard Werner as the source of it. But, as you can see, Raiffeisenbank chose not to describe Werner’s €200,000 promissory note. The vague description “Other (or Miscellaneous) Private Financing” is so ambiguous that it avoids any suggestion that Werner deposited a €200,000 document. That description doesn’t allow anyone to identify what was deposited or who made that valuable €200,000 deposit.

That Raiffeisenbank account summary lies by omission, a clear breach of its duty to keep truthful accounts, which should respect and protect the rights of both parties to the contract. It has effectively concealed Werner’s original ownership of that €200,000 security.

Banks can’t lend a bank deposit or bank credit (or customer deposit)

In the three videos above, Werner explains carefully that the newly created credit balance is not a bank deposit, was not deposited by the bank or anyone else, and was not a customer deposit. However, such erroneous and technically incorrect terms do crop up in the discussion, and seem to be justified, if for no other reason than to avoid confusing an audience with accurate accounting terms, like credit balance. Many well-meaning commentators use such common terms for similar reasons and seem to do so indiscriminately.

Such loose terminology may seem politically necessary, but it is tactically unwise, as it can only reinforce, rather than counter, the misleading implication that the bank owns that new credit balance. Even saying “credit creation by banks” or “banks create credit” also seems perfectly normal and innocent at first glance, but that too tends to imply the false claim of bank ownership in people's subconscious. The Bank of England makes this mistake repeatedly.

I don’t criticise Werner for using such common terms; I merely note the damage that can be done by tacitly accepting the implicit attribution of ownership they contain, as this terminology reinforces the error that banks can purchase the loan contract, mistakenly implying ownership of the new credit balance by the bank instead of the customer.

In my opinion, the global population has been bewitched for centuries by almost universal acceptance of this unwarranted (but popular) false assumption.

Although banks have been assuming implicit ownership of these new credit balances for several centuries and collecting interest on the matching debit balances to boot, you’ll be pleased to know that the banks are guaranteed to lose this argument when all the chips are laid on the table in a forum capable of challenging that long-standing assumption.

So, stay tuned, as I continue to unravel this centuries-old riddle so that we can take practical steps towards reasserting our ownership over all those credit balances they have pretended to lend us over the centuries.

Nothing but widespread ignorance of accounting perpetuates this ancient accounting deception, a deceitful form of theft called conversion8.

Now that we can demonstrate how this accounting fraud could remain unnoticed for centuries, even though it is openly documented in customer account statements, we should be able to find lots of different and effective ways to expose the accounting fraud and ultimately correct it.

Global awareness of the fraud should initiate the radical reformation that is needed.

The global banking system can then be rebuilt on a usury-free foundation, where promises made can be kept as slowly or as rapidly as your current means will allow, without fear of any coercive pressure or threats by a sociopathic bookkeeper pretending to be a banker. Bankers will have to get used to the idea of charging realistic fees for the public “accounting service” they provide.

Remember this!

Without our written authority, banks cannot create the credit balances they pretend to lend us.

We are, therefore, the primary cause of that credit creation process, thanks to our ability to keep the promises we make.

Our promises create the original financial value; the credit balance merely reflects that value, following the double-entry rule of accounting for our valuable deposits.

That makes us the original owners of all those credit balances, which we cause the banks to be create for us.

Our ignorance alone has allowed banks to usurp the ownership benefits, inherently attached to our innate credit-creating power.

How to counter this deception.

Educate Yourself: Do not choose to be deceived by sociopathic bank accountants. Learn the rudimentary rules of double-entry accounting to see through this most ancient illusion. The SIX basic rules of accounting you need to grasp are here, and my previous articles (see above) provide documentary evidence of HOW bank deception is achieved in specific cases.

Spread Awareness: Share this information to expose the centuries-old deception as far as you can.

Demand Accountability: When you have mastered the SIX RULES, try starting a conversation with your bank manager, who should be able to justify charging interest on your credit. Otherwise, engage politicians to explain their failure to act against a centuries-old bank accounting fraud.

Make the effort to understand why accounting logic seems so confusing. Such understanding will prompt the challenging questions that need to be asked.

No bank can prove ownership of the credit balance it claims to lend you, but you have to know the accounting rules if you want to enforce them.

Widespread awareness of the banks’ modus operandi can dismantle this deception and, if spread widely enough, will reassert our forgotten power to create credit.

Have you ever questioned your bank’s loan terms? Try asking them for proof of ownership of the credit they claim to be lending you.

Please share your thoughts in the Comments section below.

Or

Or

FOOTNOTES:

McLeay, M., Radia, A., & Thomas, R., “Money Creation in the modern economy”; Bank of England Quarterly Bulletin, 2014, Volume 54 No. 1, pp.14-22

This could be its Cash Account, for example, but it would need to have a debit balance of at least €200,000.

https://www.williamroberts.com.au/the-nemo-dat-rule/

Werner’s promise was a “naked” promise (i.e. one requiring no bank asset in return), which only creates a “debit balance”. Such a promise must be honoured, of course, but is not an enforceable “debt”.

Not that I can blame them; it took me over 70 years to take steps to understand why accounting works the way it does and start forensically investigating “How they do it”.

Werner, R.A.; “Can banks individually create money out of nothing? — The theories and the empirical evidence”; International Review of Financial Analysis 36 (2014), pp. 1–19; [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.irfa.2014.07.015]

Ok so my mind is blown. I'm a lowly off-grid rapper who grows vegies but have been aware of Werner's work for many years. I knew of his development of quantative easing for the BoJ but not this!!!

Thank you sooo much for this very enlightening article.

My music features an enduring loathing of banking fraud but now I have more to ponder and turns over to the muse

Hi Pat, I tried to summarise this article for myself - have I done it right?

If I’m not mistaken, you are saying (in a grossly oversimplified version):

“How can a bank pay Richard for a promissory note / security using money that belongs to Richard? Therefore, how can the bank be said to be “in the business of purchasing securities”? It can’t demand payment back from Richard for money that was Richard’s to begin with. So it never “paid” Richard anything (as it was Richard’s money in the first place) therefore it doesn’t make sense that Richard “owes” the bank anything. Therefore we cannot consider this a loan at all.”

Am I on the right track?

And if this is true…why are there no mass protests ?